In my previous post, we explored the importance of rest and recovery on endurance performance as well as various methods to measure fatigue and schedule one’s training sessions and mesocycles accordingly. We will now take a more detailed look into potential practices that can help maximize the quality of one’s recovery between said training sessions.

Those of you who have been active in sport at a competitive level will no doubt be familiar with the litany of recovery therapies and tools that have cropped up in recent years. I have provided a sample of these implements below:

Compression Therapy: Claimed to reduce inflammation and fluid collection in the extremities while accelerating the removal of metabolic byproducts such as lactic acid.

Massages / Percussive Therapy: Claimed to break up scar tissue, release fascia, and increase blood and lymphatic flow, thus accelerating muscle repair.

Ice Baths / Cryotherapy: Claimed to constrict blood vessels, flush waste products, and reduce inflammation as well as tissue breakdown.

E-Stim: Sends mild electrical pulses through the skin, causing the underlying nerves and muscles to “fire”. Claimed to help stimulate injured muscles and improve muscle activation.

To date, large-sample controlled randomized studies conducted on these various therapies have either turned up inconclusive and/or contradictory to each other, and the position of many coaches has been that athletes should feel free to use them if they provide peace-of-mind / a psychological benefit. However, one activity that lacks any controversy amongst both scientists and coaches is perhaps the simplest: sleep.

In the context of endurance sports, sleep plays a critical role in the recovery process. All forms of exercise, aerobic or otherwise, incur microtears in one’s muscles, the repair of which occurs most rapidly during sleep. Per my previous post, the body’s natural ability to “supercompensate”, i.e. add additional muscle cells to areas where it has sustained damage, highlights how important sleep is to making strength and performance gains. In addition, sleep accelerates the repletion of muscle and liver glycogen (readily available sugar stores, more on this in a subsequent post), normalizes hormone levels, and strengthens the body’s neural pathways to the specific muscle firing patterns one has been practicing in training.

Sleep Quantity:

Sleep requirements can vary greatly between individuals and can be affected by factors such as training load and overall life stress, but most scientists and coaches generally recommend a minimum range of 7-9 hours per night on average. Although high-level amateurs are sometimes able to reach training volumes comparable to that of professionals, professionals are able to reach higher levels of performance due to the greater amount of time they can spend getting quality sleep as opposed to balancing time commitments against a full-time job.

In addition to hitting this range, it is also often recommended to time one’s waking time with one’s sleep cycle. A single sleep cycle usually takes place over 90 minutes, during which time the body oscillates between light, rapid-eye-movement (“REM”) sleep and slow-wave “deep” sleep. The latter is most commonly associated with the benefits stated above, and my readers will most likely be familiar with the groggy and disoriented sensation one experiences when deep sleep is interrupted. It is for this reason that many doctors recommend nap times of either less than 15 minutes or greater than 90 minutes. Ensuring that one wakes up during a lighter sleep phase can be accomplished by either maintaining a consistent sleep schedule or more conveniently, utilizing alarm applications that automatically detect one’s sleep phase. Experiments have also indicated that one cannot “bank” on sleep, i.e. sleeping longer now in anticipation of future periods of sleep deprivation.

From my personal training experience, I have found that getting 8 hours a night is ideal but have often been able to get by with as little as 7 hours in a pinch. Anything below this and I have typically seen either a plateau or even a dip in performance on harder sessions.

Sleep Quality

In recent years, scientists have studied ways to improve both the time it takes to fall asleep and propensity to stay asleep. For example, minimizing exposure to blue light (e.g. reducing electronic device screen time and using blackout shades) prior to going to bed has been found to increase sleep-promoting melatonin levels. In addition, maintaining a cooler core temperature and playing ambient noise to drown out potential disturbances have also been found to have positive effects. Interestingly, while alcohol has been found to assist in falling asleep, it is also very disruptive to the REM phase of the sleep cycle, resulting in a greater propensity of waking up. With the advent of wearables such as smart watches, numerous apps have been developed to monitor both the quantity and quality of one’s sleep and the potential impact on one’s ability to hit key sessions.

Active Recovery / Injury Prevention

Expanding on the hypothesis we explored in a previous post that training consistency is one of the most important determinants of success in endurance sports, I have found that one of the keys to maintaining training consistency over the course of a season has been staying free from injury. Over the course of my first two seasons as a newbie, I experienced the full gamut of injuries ranging from minor niggles to conditions taking months to recover from, including but not limited to: shin splints, plantar fasciitis, patellar / peroneal tendonitis, and lower back pain. After a great deal of trial and error, I greatly attribute my breakout performance at Ironman Wisconsin to simply being able to keep such issues in check with by performing certain activities during the time between training sessions. While the mileage of my readers may vary, below are a few of the lessons I learned through the process on avoiding major setbacks:

- Performance Management Chart: As outlined in my previous post, the Coggan PMC chart is an incredibly useful tool to ensuring that one does not increase training volume and/or intensity at a rate beyond the body’s ability to recover. In my case, I have historically found that allowing my training stress balance value to drop below -40 tended to result in excessive fatigue as well as a greater propensity for injury.

- Warmups: Experiments have shown that warmup routines reduce the chances of injury by reducing the initial brittleness of muscle fibers via increased blood flow. I have also found warmups helpful in that they provide sufficient time for my mind to brace for difficult sessions. Every athlete has their own routine, but my warmups are typically comprised of 5-10 minutes of swimming / biking / running at a very easy pace combined with technique work and dynamic stretching (see below).

- Technique: It goes without saying that poor form can oftentimes lead to excessive strain to muscles and tendons that are not being used properly. This is particularly the case for high impact sports such as running, where common mistakes such as over striding and heel-striking can significantly increase the forces absorbed by one’s ankles, knees and, hips. For this reason, I’ve found that incorporating drills into my warmups (e.g. stride-work for running, cadence drills for cycling, and various pool toys for swimming) provides a good reminder of proper technique prior to executing the meat of one’s main set in training sessions. As a personal anecdote, one particular muscle group that has given me trouble in the past has been my glutes, a direct result of my sedentary desk job. If my glutes are not properly activated (which can take as long as 10-15 minutes!), this has oftentimes led to excessive strain to other muscles groups such as the hamstrings and calves, resulting in issues such as shin splints.

- Mobility: Because muscle and joint mobility is critical to the upkeep of said technique, over the years, I have come to allocate a material amount of time each day (~30 minutes) to static stretching and foam rolling. Ensuring a sufficient range of motion not only ensures that individual fibers do not get unnecessarily strained, but can also provide potential performance gains (e.g. a more aerodynamic position on the bike and greater pull distance in the swim). Typical muscle groups that I tend to target include the hip flexors, glutes, quads, hamstrings, calves, and lats, typically in intervals of over 2 minutes. It should be noted that a distinction must be made between traditional static stretching (i.e. holding a muscle steady in a lengthened position for a certain amount of time) vs. dynamic stretching (e.g. leg swings). Recent studies suggest that static stretching can increase risk of injury if performed prior to a workout.

- Strength Work: In a similar manner to technique, muscle weakness and imbalances in certain areas of the body can oftentimes result in other muscle groups overcompensating, which can in turn lead to overuse injuries. To help their athletes avoid this issue, many coaches oftentimes establish certain minimum strength benchmarks. Below are the benchmarks I have adhered to over the past few seasons as prescribed by Trainerroad (more on them on a subsequent post).

To the cross-fitters and weightlifters amongst my readers, these requirements will likely seem to be laughably easy and perhaps even deserving of the #doyouevenlift Instagram handle. The purpose of these sessions however is not to maximize strength but to maintain a minimum level of functionality in key muscle groups associated with swimming, biking, and running. In addition, weightlifting is also generally known to develop fast-twitch as opposed to the slow twitch muscle fibers desirable for endurance sports, which in turn reduces energy efficiency and one’s sustainable power to weight ratio.

- Physical Pain: Before diving into this, I must issue the mandatory disclaimer that my readers should most certainly seek medical attention from a qualified doctor or physiotherapist if they experience training-related discomfort. With that out of the way, I wish to share two high-level learnings from my own experience and many doctor visits over the past few years:

- “Good” vs. “bad” pain: While all exercise causes bodily damage to some extent and pain is the body’s natural mechanism to protect itself from injury, one of my most important lessons from the past few seasons was learning to distinguish between pain that one can safely train through and pain that is indicative of long-term, chronic bodily damage. As a general rule of thumb, I have found that the “burning” sensation that one experiences when working at intensities above threshold is the result of blood acidification as opposed to muscle damage and almost always disappears once one has spent sufficient time at a lower intensity for the body to return to equilibrium. For pain that lasts longer than this, I have also found that one needs to make a distinction between pain that comes from the muscles vs. from one’s joints / tendons. For the former, I have found that if the soreness does not last more than 2-3 days or tends to subside once one has warmed up, it is safe to train through. Joint / tendon pain on the other hand is usually a major red flag, in which case I typically reassess whether there are any strength or mobility deficiencies in any of my movement patterns.

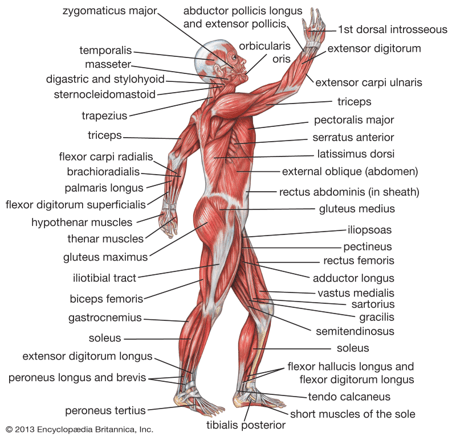

- Kinetic Chain: Another key lesson I’ve picked up along the way is that the cause of pain is oftentimes not the same as its source. For example, I discovered that my multiple cases of plantar fasciitis (pain in the arch of the foot) were caused by excessive tightness in my calves. Similarly, my patellar tendonitis (pain in the kneecap) was due to an imbalance in strength between my various quad muscles. Likewise, chronic back pain that I experienced on the bike was the result of a weak glute medius. Through these experiences, I have found that developing a working knowledge of how various muscle groups are connected and interact via anatomy charts from books and/or the internet can help one decide how to adjust one’s strength and/or stretching protocols to address the issue, or failing that, assist medical professionals in narrowing their diagnosis as opposed to relying on trial and error.

In my next post, we will begin to explore the world of triathlon equipment, with a specific focus on the tools that I’ve found most useful in the training process. In the meantime, for those of you who would like to follow my training progress, most of my sets can be found on my Strava account at: https://www.strava.com/athletes/15134014.

#dacakeisalie

One thought on “Entry 6: Rest and Recovery Part 2, Recovery Activities”