After an extended hiatus, it is now time to get back in the saddle, both literally and figuratively. As many of you may have heard, the Kona Ironman World Championship originally scheduled for October 2020 was postponed to February 2021 due to the extent of the COVID-19 pandemic. Given the high likelihood that mass events will not take place until a vaccine is in circulation, I have instead elected to defer my qualification to the 2021 edition of the race being held next October. While certainly a disappointing outcome, I do believe that this was the right call for the safety and wellbeing of participants, spectators, and kama’aina alike. In addition, this postponement provides an incredible opportunity to experiment with new training protocols to potentially reach even greater heights of performance, which we will explore in detail in this post.

Low Intensity Training – 80/20 Principle

In studies conducted in the early 2000s, sports scientists like Stephen Seiler and Augusto Zapico found that on average, elite-level endurance athletes across a variety of sports (e.g. cross country skiing, rowing, swimming, cycling, and running) devoted a surprisingly large amount of time (~80% of sessions and ~90% of total hours) to low-intensity training, low intensity being defined as work executed below the first ventilatory threshold (“VT1”). In laymen’s terms, this is often described as an intensity where one can easily hold a conversation or breathe through one’s nose. Using the training zones described in a previous post, this would be roughly equivalent to Zone 2 and below. The remaining 20% of sessions and/or 10% of hours was spent above VT1. Dr. Seiler theorized that this “80/20” distribution has emerged amongst elite endurance athletes as the outcome of a natural selection-like process, i.e. in the 150 years since endurance sports took on their modern form, a large number of training intensity distributions have been tried and pitted against each other in high-stakes international competition, the inferior methods of which have been discarded.

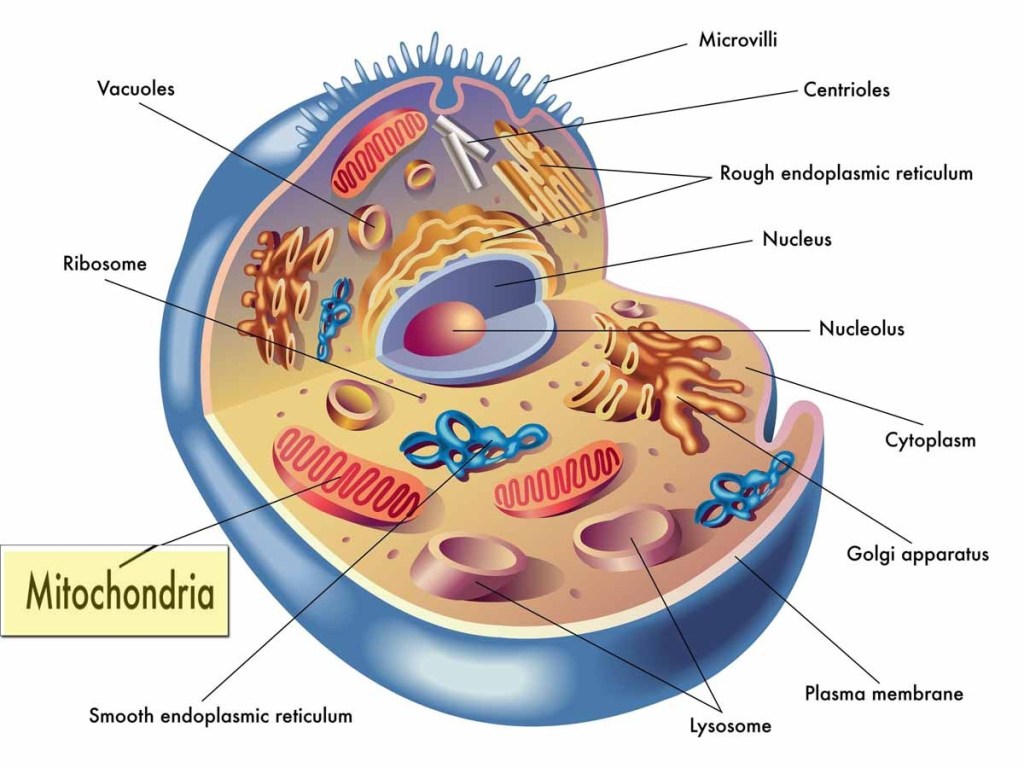

In contrast to the pros, surveys indicate that most recreational triathletes spend a much lower percentage of time (68% on average) at low intensity. I myself have been guilty of this over the past few seasons, due to a combination of (i) a lack of discipline (let’s face it, no one likes to get passed by grandma on the road and zone 2 is embarrassingly slow) and (ii) the belief that the 80/20 distribution only applies to pro-level training volumes and that one can compensate a lack of training volume with increased intensity. Nevertheless, controlled-randomized experiments such as that conducted by the University of Salzburg have found that athletes executing a training program most skewed towards the 80/20 benchmark had the greatest improvements in VO2max, time to exhaustion, peak cycling power, and peak running velocity over a nine-week period. Furthermore, follow-up studies also suggest that these performance gains are scalable across a variety of training volume levels. In terms of why this distribution seems to be the most efficient, it has been suggested that not only does a proportionally large amount of low-intensity training increase one’s muscle mitochondria count (the powerhouses of the cell), but also ensures that the athlete is fresh enough to execute higher intensity sessions with greater compliance and quality.

Based on these findings and the additional time between now and Kona, I have taken the leap of faith to see whether the 80/20 distribution will lead to improved performance. For example, while my previous training plan called for 1 easy, 1 medium, and two hard rides per week, over the past few months, I have changed this to 3 easy rides and 1 hard ride per week. While initial performance improvements have been promising (e.g. FTP has risen from a trough of 280 watts after taking some time off to 291 watts, greater than my pre-Wisconsin peak), time will tell whether effectively going slower in training will allow me to go faster on race-day.

Medium vs. High Intensity Part 1: Underlying Science

Having established the need to ensure that 80% of training is executed at low intensity, the question then arises of how to distribute the remaining 20%. To put it differently, is this time best spent at medium or high intensity or perhaps some combination of both? Based on my read of the scientific literature to-date, the answer seems to be “it depends”. Given the technical nature of this exploration, for this next section I have highlighted the key takeaways for my TLDR readers.

As discussed in a previous post, one of the key limiting factors to endurance performance is one’s lactate threshold, i.e. the exercise intensity at which the body’s production of lactate overwhelms its ability to clear it, as illustrated in figure 1 below. One may recall that an accumulation of lactate causes the unpleasant “burning sensation” that eventually forces the body to slow down.[1]

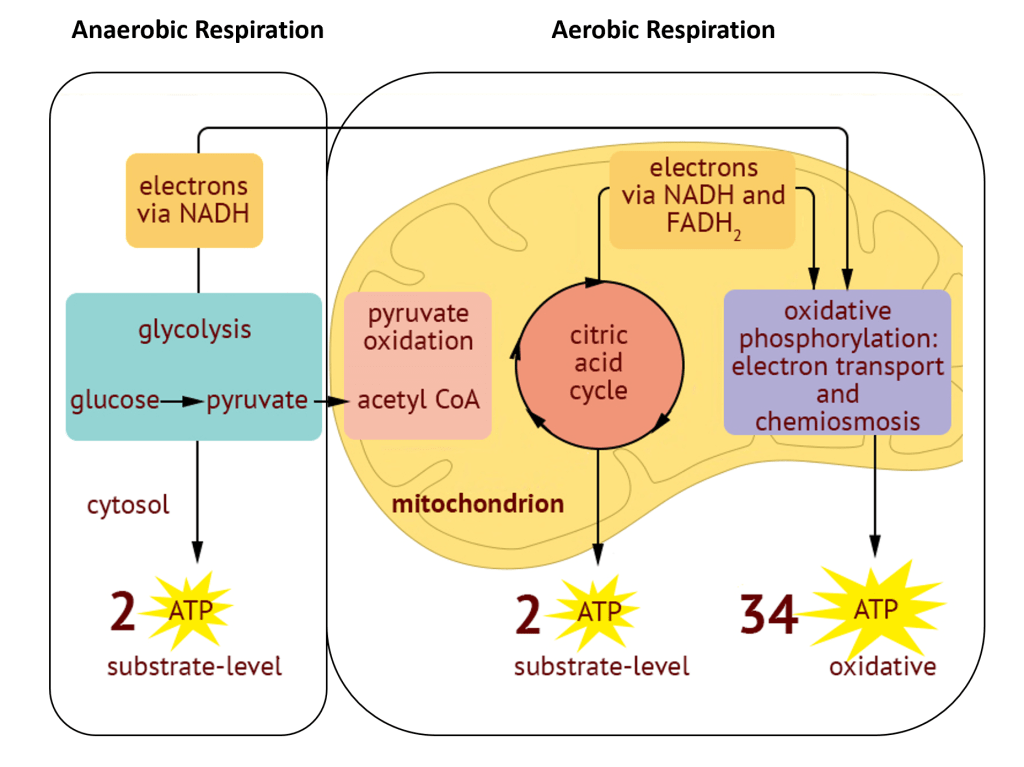

A better understanding of this dynamic requires a quick throwback to high-school biology class. For the purposes of endurance sports, the human body is able to generate energy in two principal ways.

- Anaerobic Respiration: through a process known as glycolysis, cells break down glucose (sugar) molecules into pyruvate, resulting in a net gain of 2 ATP (the energy currency of the cell). While this process is quick and does not require oxygen, the resulting pyruvate molecules are converted into lactate and shuttled into the bloodstream if they are not immediately used by the 2nd energy production method below.

- Aerobic Respiration: utilizing either the pyruvate molecules generated by glycolysis above or the byproducts from the breakdown of fat, cells combine these with oxygen to produce 36 additional net ATP over multiple cycles. Unlike anaerobic respiration which takes place in the cytoplasm (the gooey no-man’s land within the cell), aerobic respiration takes place within the mitochondria.

The key takeaway here is that anaerobic respiration produces lactate while aerobic respiration clears lactate. With this in mind, the human body has various kinds of muscle fibers that utilize these energy production methodologies in different proportions:

- Type I: Also known as slow-twitch fibers, these muscle cells have a high concentration of mitochondria and therefore rely more on aerobic respiration. These fibers are very good at producing low / moderate force contractions over long periods of time.

- Type IIx: More commonly known as fast-twitch fibers, these muscles have a lower concentration of mitochondria and therefore rely far more on anaerobic respiration. These fibers are very good at producing high force contractions over short periods of time.

- Type IIa: These are intermediate type fibers that can be trained to be more akin to type I and type IIx fibers depending on external stimuli.

As such, an athlete’s lactate production for a given intensity level is strongly driven by his or her proportion of fast-twitch muscles. The more fast twitch muscles, the more lactate one tends to produce. While the most accurate way to measure this proportion is via a muscle biopsy, one can also measure Vlamax (maximum production rate of lactate) via a maximal sprint test as a proxy.

Although lactate production is driven by the proportion of fast-twitch fibers, the corresponding proportion of slow-twitch muscles does not necessarily determine one’s lactate clearance rate, as aerobic respiration is more constrained by the body’s ability to deliver oxygen to individual muscles cells. This is driven by factors such as lung capacity, the efficiency of gas exchange at the lungs, the stroke volume of one’s heart, red blood cell count, and muscle capillarization. Conveniently, all of these factors can be summarized by a single variable, Vo2max, which measures the maximum amount of oxygen that one can utilize during intense exercise as described in a previous post.

To summarize what we’ve gone over so far, lactate production is determined by one’s proportion of fast-twitch muscle fibers (measured by Vlamax), while lactate clearance is determined by one’s aerobic capacity (measured by VO2Max). The exercise intensity where these two lines intersect, at which point lactate starts to accumulate and forces the athlete to slow down, is known as the lactate threshold. All this has been summarized in figure 6 below.

Using this framework, one can see that there are two possible ways to increase one’s lactate threshold: (i) by increasing one’s aerobic capacity (increase Vo2Max, figure 7) or (ii) by decreasing one’s proportion of fast-twitch fibers (decrease Vlamax, figure 8).

Having addressed the underlying science, we can now examine what training protocols can be used to accomplish these ends.

Raising one’s Vo2max can be accomplished with the following training protocols:

- High training volume at low intensity (already accomplished by 80/20 distribution rule)

- High-intensity intervals (threshold and Vo2max zones, i.e. 100%-120% of threshold)

Lowering one’s Vlamax can be accomplished with the following training protocols:

- Medium intensity intervals (high tempo / low threshold zones, i.e. 88-94% of threshold)

- Strength-endurance work (e.g. hill runs, low cadence rides)

- Low-glycogen training (e.g. fasted rides)

It should be noted however, that maintaining a high Vlamax may be desirable for certain race formats such as draft legal triathlons, road races, and other applications that require frequent anaerobic surges to bridge gaps and chase down breakaways. For these athletes, the only viable path to increasing anaerobic threshold is raising Vo2max.

Medium vs. High Intensity Part 2: Personal Case Study

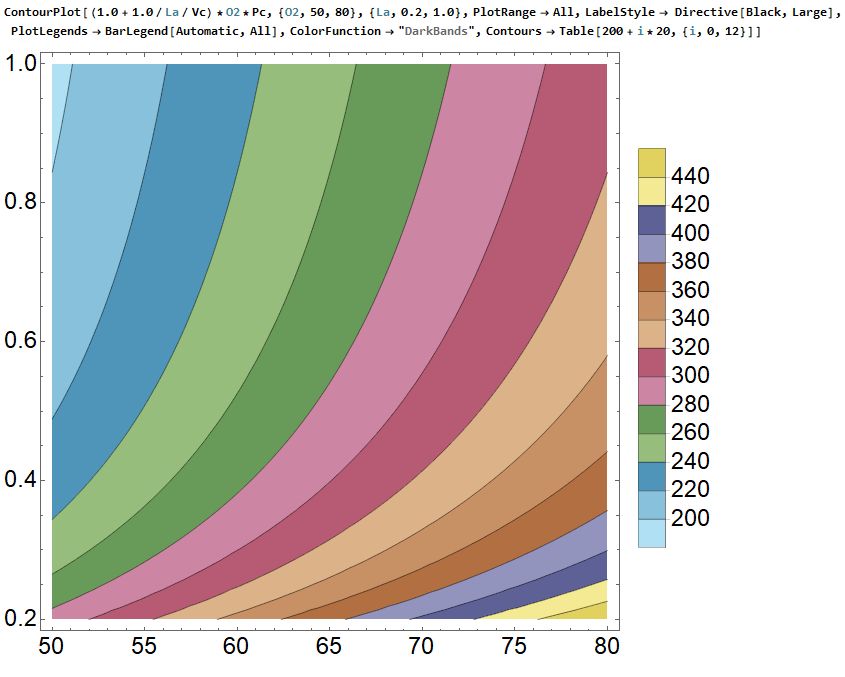

Returning to the original question of how an athlete should distribute the remaining 20% of his or her training time, the answer is dependent on the amount of “room” one has to improve in each metric. Using myself as a case study, a recent battery of fitness tests I executed on the Inscyd platform measured my cycling Vo2max at 67.4ml/min/kg and Vlamax at 0.52mmol/l/s.

Based on the rule of thumb that one’s cycling Vo2max is often marginally lower than one’s running Vo2max and the fact that my running Vo2max has consistently been tested at around 70ml/min/kg in the past suggests that my Vo2max is close to maxed out. By comparison, my Vlamax is materially higher than what would be considered optimal for a long-course triathlete (typically in the 0.30 range), suggesting significant room for improvement via the conversion of fast twitch to slow twitch fibers. This comes as no surprise given my collegiate squash background, which involved a significant amount of anaerobic microintervals. The Inscyd test results thus suggest that the remaining 20% of my time should be spent doing medium intensity intervals, strength endurance work, and fasted training. Using the below contour chart reverse-engineered from Inscyd’s model, a reduction in Vlamax from 0.52 to 0.30 could potentially result in a threshold increase from 290 watts to ~330 watts, a nearly 14% improvement.

It should be noted that the hypotheses that I have drawn in this post are merely based upon my personal collation of the latest research in sports science. Not only may my interpretation of this body of knowledge be incorrect (and I readily invite my readers to correct any errors I have made), but like all science, our understanding of the human body is itself subject to constant change and refinement. Nevertheless, the extra time between now and Kona provide a unique opportunity to see whether these theories work in practice, and I will certainly be sure to keep my readers informed on my progress in this journey.

In my next post, we will explore the importance of daily and race-day nutrition on performance. In the meantime, for those of you who would like to follow my training progress, most of my sets can be found on my Strava account at: https://www.strava.com/athletes/15134014.

#dacakeisalie

[1] For the more scientifically minded amongst my readers, technically the burning sensation is caused by blood acidification as a result of excess hydrogen ions but this has been found to be directly proportional to lactate, which is used as a proxy.

2 thoughts on “Entry 9: Training Plan Part 3, Addendum”