In spite of its name, a strong argument can be made that the sport of triathlon is comprised not just of three disciplines but four – being as much an eating and drinking contest as it is a test of prowess in swimming, biking, and running. In this post, we will explore how both race-day and everyday nutrition and hydration play a critical role in going the distance.

Nutrition

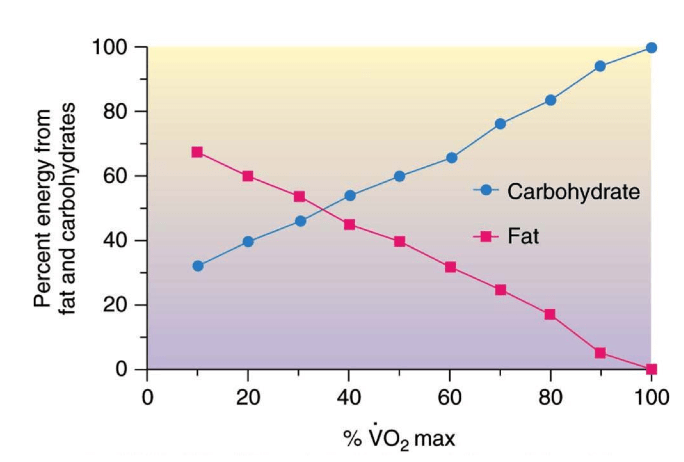

As mentioned briefly on previous posts, endurance performance is powered by the consumption of two primary fuel sources: fat and carbohydrate. As exercise intensity increases, one’s body must burn proportionally more carbohydrate given that it is much easier and faster to metabolize than fat. The limiting factor here is that the human body can only store a finite amount of carbohydrate for immediate use, predominantly in the form of glycogen in both the bloodstream and the liver. Once this supply of carbohydrate is exhausted, the body is forced to revert back to fat metabolism, resulting in a dramatic decrease in performance known colloquially as “bonking” or “hitting the wall”. Additional symptoms of glycogen depletion include nausea, disorientation, tunnel-vision, heart palpitations, and of course: extreme “hangryness”. Those of my readers who have experienced this phenomenon before would be quick to describe it as one of their least pleasant life experiences.

For this reason, periodically topping off carbohydrate stores is critical for sustaining one’s effort during both races and longer training sessions. Before someone goes and wolfs down an entire birthday cake in the middle of a hard training session however, it should be noted that the human gut has an upper limit to the rate at which it can digest carbohydrates. For a single carbohydrate (e.g. glucose), this is typically quoted at around 60-70 grams per hour. If one consumes a variety of carbohydrates (e.g. glucose + fructose), this can be boosted to as much as 100 grams per hour. It should be noted that achieving these absorption rate levels, particularly during exercise, does not happen overnight and requires extensive practice.

In addition to maintaining carbohydrate stores, an athlete can also extend the duration of his/her performance by increasing the overall proportion of fat as opposed to carb burned across all intensity levels through training. Unlike carbohydrate, fat is for all intents and purposes an infinite resource for a one-day race unless one is chronically malnourished. In my previous post, we took a deep dive into cellular respiration and the difference between slow-twitch and fast-twitch muscle fibers. Because slow-twitch fibers are better adapted than fast-twitch fibers towards burning fat, shifting one’s muscle composition to the former can pay dividends in maintaining a specific intensity for longer periods of time and/or reducing one’s carbohydrate fueling requirements. In this way, while most recreational athletes can maintain a moderate effort for 1.5-2 hours before hitting the wall, many professionals have achieved fat adaptation levels that allow them to extend this effort to over three hours. As mentioned previously, ways of shifting one’s muscle composition in this manner include the following:

- Medium intensity intervals (high tempo / low threshold zones, i.e. 88-94% of threshold)

- Strength-endurance work (e.g. hill runs, low cadence rides)

- Low-glycogen training (e.g. fasted rides/runs)

Hydration

In a similar manner to nutrition, hydration also plays a critical role in endurance performance. Over the course of training and/or racing, the body sheds fluids through both sweat and respiration, which must be replaced in order to maintain a high level of intensity over an extended period of time. While most of my readers would be familiar with the importance of water for both bodily and cell-level functions (water comprises ~60% of body mass), an oft-overlooked aspect of hydration is the maintenance of one’s balance of electrolytes (salts), which are also lost through one’s sweat. Of the many types of salt that the body utilizes, sodium plays a particularly crucial role in the activation of nerve cells. As such, simply drinking plain water to replace fluids over the course of a long bout of exercise can dilute the body’s sodium concentration levels, leading to a condition known as hyponatremia which in extreme cases can lead to a loss of consciousness and death.

The amount of fluids that one sheds over time varies significantly between athletes and is also subject to outside factors such as ambient temperature and humidity. Typical exercise sweat rates can range between 0.5-2.5L per hour. An easy way to measure one’s own sweat rate is by comparing one’s body weight before and after a workout, with every kg (2.2lbs) reduction corresponding to approximately 1L of water lost.

The amount of sodium lost with this fluid can also vary significantly between athletes but is relatively constant across external conditions. Typical values can range between 200-2,300mg/L of sweat lost. Finding this value typically requires getting a sweat test at a nutritionist or fitness lab.

Case Study: My Race Fueling Plan

With the basics established, we can now dive into the framework I used to develop my own nutrition and hydration plan for race day. First, the parameters: the metabolic profile provided by my tests with Inscyd (explained in greater detail in my previous post), indicates that at target Ironman intensity, my body burns approximately 70-80g of carbohydrate per hour, while sweat tests indicate that I lose approximately 1L of sweat per hour and that each liter of sweat contains 1126mg of sodium.

Based on prior experience, I have found in that I am able to meet all these requirements with the products provided by aid stations placed in regular intervals throughout both the bike and run courses. My hydration requirement is fulfilled by drinking slightly more than one Gatorade Endurance bottle (24oz, 710ml) every 45min. At this rate, Gatorade Endurance also provides 30g of carbs and 827mg per hour. On the bike, this is supplemented with 1 packet of Clif Bloks per hour, which provides an additional 46g of carbs and 300mg of sodium to hit my targets. On the run, I have historically found it difficult to digest solid food (something learned the hard way at Ironman Lake Placid!), for which reason I instead ingest two packets of Gu Roctane gels per hour. Because these gels do not provide quite enough sodium, I supplement this with a salt tab which I periodically lick to achieve the balance of that target.

In terms of how this all works logistically, it goes without saying that it is extremely difficult to take in any form of hydration or nutrition during the swim. For this reason, the bike portion of the race is particularly critical to making up that deficit and ensuring that one has sufficiently topped off the tank to complete the marathon. As mentioned on a previous post, while many athletes elect to carry their own custom-tailored nutrition and hydration products (triathlon bikes are sometimes jokingly referred to as buffets on wheels), I have personally found that periodically replenishing one’s supplies at aid stations is much faster. Not only does this save a great deal of weight (each bottle weighs half a kilo!) but it also allows me to maintain a cleaner, more aerodynamic bike frame.

During the run-portion of the race, most Ironman athletes generally take in both their hydration and nutrition at aid-stations. However, I have personally found this approach to be difficult as I am often unable to ingest a sufficient amount of fluids from the open cups served by said aid stations without coming to a complete stop. To solve this issue, over the past two seasons I have trained and raced with a hydration vest, which enables me to completely bypass aid stations. This proved to be a very successful strategy at Ironman Wisconsin last year, where I had the fastest run split of the day despite the extra weight.

General Diet

While there have been a large number of diet trends that have arisen over the past few years (e.g. intermittent fasting, keto, vertical, plant-based, paleo, etc.) and a wide variety of recommendations on the distribution of macros (protein, fats, and carbs), I have for better or for worse not followed any specific philosophy on this front. Over the past few seasons, I have simply aimed to have balanced meals generally comprised of some form of meat, veggie, and carb-base, ideally from whole as opposed to processed food sources. Aside from a substantially higher calorie count, the only major difference from a standard diet worth mentioning is with regard to the timing of meals. While most of my readers would be familiar with the unpleasant “stitch” that develops when one exercises too soon after a major meal, between 1.5-2 hours following a meal, the body’s insulin level spikes to store glycogen in the liver, resulting in a temporary depletion in blood glycogen levels (in more colloquial terms, “food coma”). For this reason, I have found that the most optimal time to exercise is after this two hour mark. In addition, after a training session, the body’s ability to absorb nutrients remains substantially elevated for approximately 20-30 minutes, providing a window of opportunity to fast-track digestion and recovery ahead of one’s next session.

In my next post, we will take a break from the technical side of things and explore some of the more lighthearted and cultural elements of the sport of triathlon. In the meantime, for those of you who would like to follow my training progress, most of my sets can be found on my Strava account at: https://www.strava.com/athletes/15134014.

#dacakeisalie

One thought on “Entry 10: Fueling the Furnace”