In a previous post, I noted that while there is an endless variety of recommendations on how to prepare for an Ironman, the common thread amongst many coaches is that ahead of any specific guidance on training intensity or volume, training consistency is perhaps the most important determinant of success. Given that triathlon is predominantly an outdoor sport, one of the key points of friction to training consistency is naturally the weather. Fully acknowledging the irony that spring (and with it, hopefully some racing!) is finally upon us here in the northern hemisphere, in this post we will explore the various options that I have found most helpful over the past few seasons when the weather outside was less than cooperative.

Swim:

While open water swimming becomes an important factor closer to race day (typically during the late spring and summer), the bread and butter of swim training typically takes place in the controlled environment of the indoor pool. Nevertheless, recent pool closures due to COVID19 lockdowns have forced many athletes to improvise, including, for some brave souls, hitting the beach during the colder months. This is entirely feasible with the appropriate equipment, namely thermal wetsuits, insulated caps, gloves, and booties. While standard wetsuits can provide adequate insulation down to 55-60° Fahrenheit (12-16° Celsius), thermal wetsuits can in some cases be used in arctic conditions, although more race-focused models are usually rated down to 45-50° Fahrenheit (7-10° Celsius). These are routinely used at races such as the Isklar Norseman Xtreme Triathlon, an Ironman-distance event where the swim takes place in a Norwegian fjord that is known to get as cold as 50° Fahrenheit (10° Celsius). The Norseman is generally considered one of the most challenging race courses in the world.

Bike:

Before diving into this topic, it is necessary for me to invoke rule #9 issued by the Velominati (cycling’s definitive governing body): https://www.velominati.com/:

#9: If you are out riding in bad weather, it means you are a badass. Period. Fair-weather riding is a luxury reserved for Sunday afternoons and wide boulevards. Those who ride in foul weather – be it cold, wet, or inordinately hot – are members of a special club of riders who, on the morning of a big ride, pull back the curtain to check the weather and, upon seeing rain falling from the skies, allow a wry smile to spread across their face. This is a rider who loves the work.

With that disclaimer out of the way, while there may be some riders out there with the cojones to ride year-round, the risk of catastrophic injury due to black ice, narrow road shoulders, and windchill are such that I have generally opted to do my winter riding indoors. Over the past few years, extensive progress has been made in both software and hardware to make the indoor riding experience significantly more tolerable.

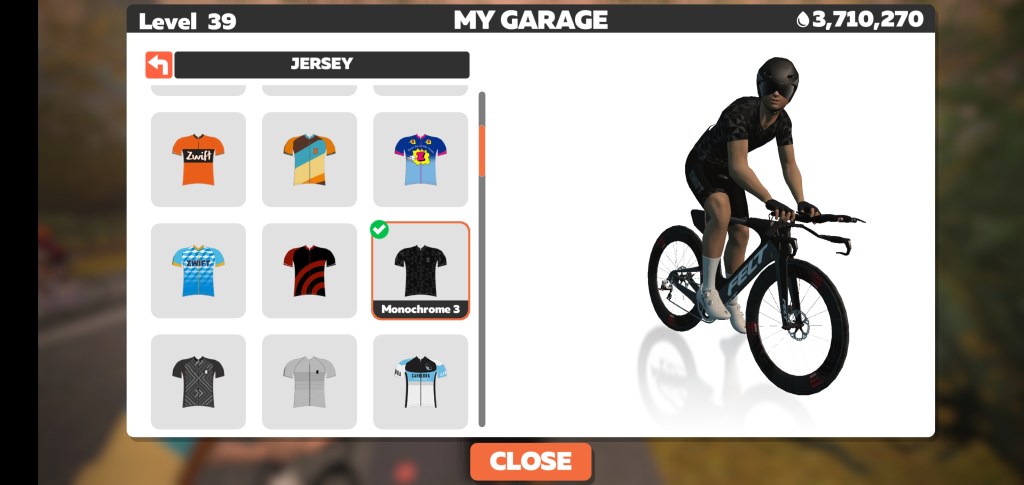

- Software: over the past few seasons, I have extensively utilized Zwift, which is a computer program that provides a variety of immersive virtual courses where cyclists can train. Zwift also has a number of social features which enable athletes to organize group rides with their friends as well as race with fellow competitors worldwide. As of February 2021, Zwift has over 3 million subscribers around the world, with peak volumes of 45,000 simultaneous users. To incentivize greater participation, Zwift has “gamified” the training experience by setting up a virtual currency within the platform which users can earn through the accumulation of mileage and unlocking various achievements (e.g. winning races). This currency can then be used to purchase virtual gear and outfits. To date, I have personally logged over 21,000 miles on Zwift, hit the max level cap, and managed to unlock the bike setup that I intend to use at Kona. It should be noted that Zwift is not the only virtual cycling platform. Other products available in the market include TrainerRoad, TheSufferFest, Rouvy, BKool, and FulGaz.

- Hardware: In order to participate on these software platforms, one generally needs to use an indoor bike trainer, which either comes as a standalone unit or as a bolt-on to one’s outdoor bike setup. Cheaper “dumb” trainer options simply provide a pre-set ramp of resistance to pedal against. Higher-end “smart” trainers provide additional immersive elements such as grade changes (e.g. climbing a 10% grade hill in Zwift results in the trainer automatically adding resistance) or road surface simulation. In addition, smart trainers also offer the option of “erg” mode, which locks the rider into a preset power output, backing off the resistance if the rider pedals too quickly and applying additional resistance if the rider pedals too slowly. I have found this feature immensely useful for maintaining my power targets during sessions involving longer, submaximal intervals. A word of warning however: erg-mode can be highly demoralizing when used for high-intensity interval sessions above threshold due to the affectionately-named “spiral of death”. In this situation, a tired rider who is no longer able to maintain the preset power target naturally slows down his pedaling cadence. In response to this reduction in cadence, the trainer increases its resistance, which can result in a cascading feedback loop that forces the rider to come to a grinding halt. For this reason, I generally opt out of erg mode for high intensity sessions.

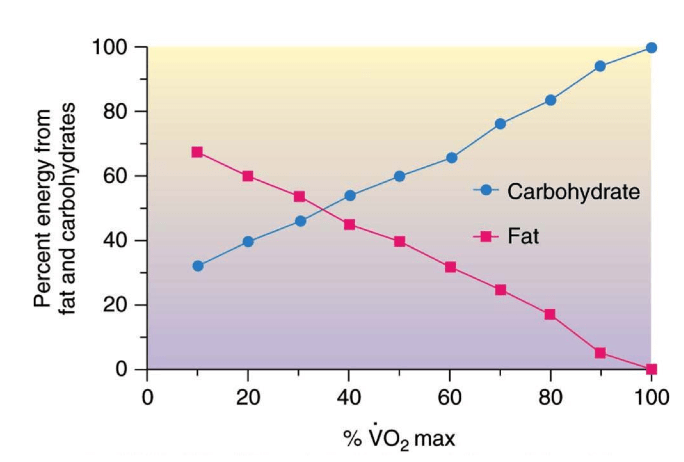

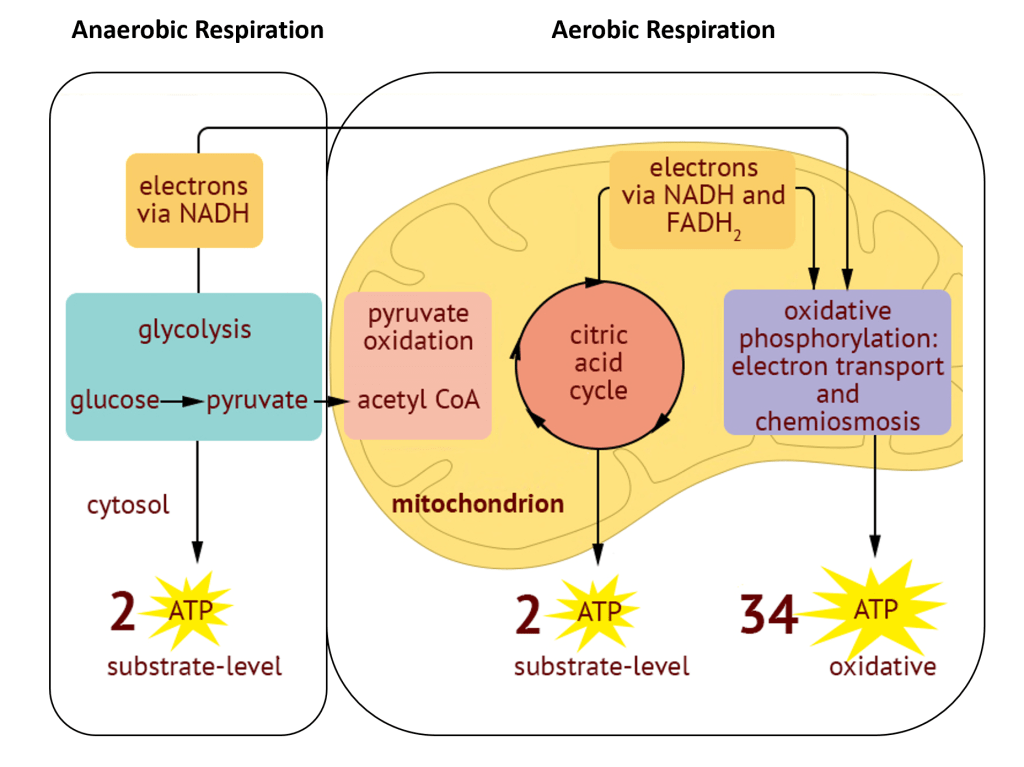

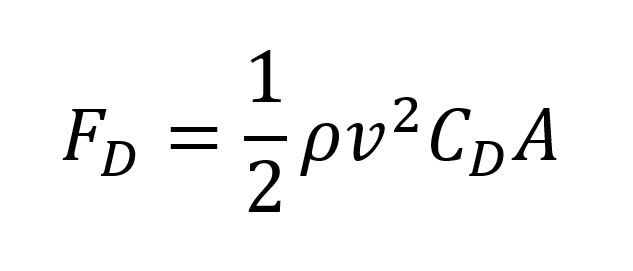

It is well known amongst coaches and physiologists that most cyclists are not able to generate the same power output indoors as they can outdoors. This can generally be attributed to two main factors:

- Heat: when riding outdoors, cyclists benefit from the cooling effect of the oncoming rush of air as long as they maintain a respectable speed. This is not the case when riding indoors as one is pedaling in a static position. In order the stay cool, the body is forced to sweat more (resulting in greater dehydration) and to send additional blood to the skin instead of the working muscles. One way to partially mitigate this reduction in performance is to install a powerful fan for one’s indoor setup, which greatly assists the body’s ability to shed heat through increased airflow.

- Flywheel inertia: While all cyclists strive to achieve as even a pedal stroke as possible, the reality is that every pedal stroke is made up of many micro-accelerations and decelerations. When one stops or slows down one’s pedal stroke when cycling outside, the rear wheel / hub continues to spin in accordance to Newton’s first law (an object in motion stays in motion unless acted upon by an outside force). As a result, the amount of additional power needed to maintain a specific wheel / hub speed is relatively small. Many indoor trainers lack this inertia however, the worst offenders being gym spin bikes which utilize either physical pads or magnets to apply resistance directly to the hub. Because their hubs slow down materially faster when one’s pedal stroke decelerates, these trainers require more effort from the rider to maintain a specific wheel / hub speed. As such, the best way to mitigate this issue is to purchase an indoor trainer that has a very heavy flywheel that can simulate the inertia of outdoor riding. These do tend to be more expensive and (unsurprisingly) more difficult to transport.

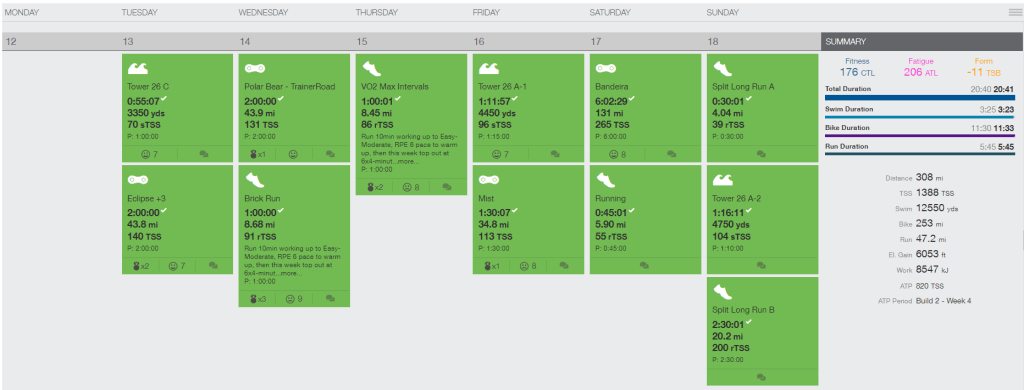

In terms of my personal setup, I currently use the Tacx Neo 2, which is a smart trainer with a heavy flywheel and a good reputation for power accuracy. This is directly hooked up to Zwift onto which I have manually uploaded my prescribed workouts (typically executed in erg mode except my VO2Max sessions). In front of this I have a desk which holds a fan for cooling as well as a laptop / iPad for entertainment. To pass the time, for shorter sessions, I typically listen to audiobooks and podcasts (e.g. That Triathlon Show, TrainerRoad, and MX Endurance), while on longer sessions I usually watch movies and TV shows. Having completely emptied the Amazon / Netflix / HBO archives, any content suggestions would be much appreciated!

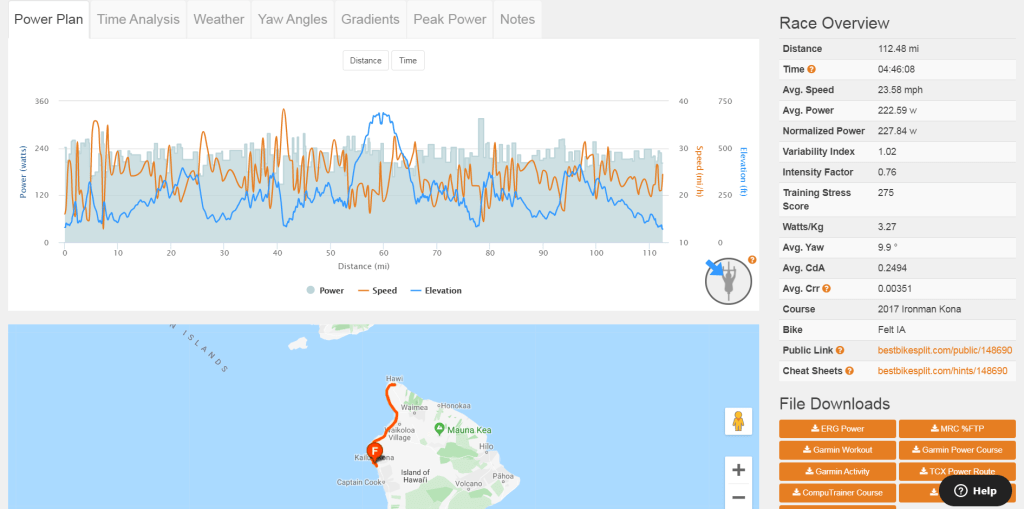

Cycling indoors no doubt has many advantages. In addition to providing a way to train in inclement weather, it also significantly reduces the setup time between rides and provides a safe environment free of car traffic and traffic lights that allows athletes to more closely hit their prescribed intervals. That being said, this is not to completely rule out the utility of outdoor rides, which are essential for developing bike handling skills, pacing, as well as race day tactics.

Run:

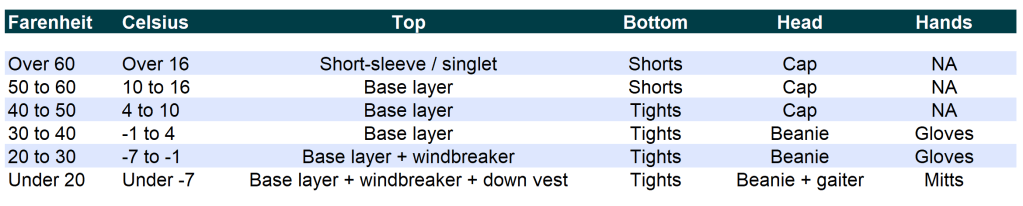

Unlike with cycling, I have found that running outdoors throughout the year is completely viable in all but the most extreme of weather conditions and is generally a matter of dressing appropriately. In the below table, I have laid out what I have generally worn outdoors across various temperature ranges (note: my thicker-skinned colleagues in the American mid-west and Canada will likely claim that they can run in shorts at below freezing temperatures).

As a general rule of thumb, I have found that dressing in what one would normally wear on a casual basis if the temperature was between 15-20 degrees Fahrenheit (8-11 degrees Celsius) warmer to be good guidance. Historically, I have found that if I feel a little chilly prior to warming up, I have usually dressed appropriately. This ensures that the body does not overheat while running, which can produce excess sweat that can be dangerous if one is forced to stop in the middle of a session on a cold day. For this reason, one should also consider a lighter wardrobe for harder run sessions as these will produce more body heat. For runs involving heavy rain or snow and ice, swapping out one’s trainers for a set of light trail shoes can go a long way in terms of providing protection against the elements as well as increased traction.

Treadmill running can also be an effective training tool and was something I utilized extensively in the preparation for Ironman Wisconsin, making up the majority of my run training. In addition to allowing the user to lock-in a pace, similar to indoor bike training, treadmills provide a highly controlled environment where one can execute one’s intervals with greater precision free of interruptions. However, I would like to point out two pitfalls that I have encountered from treadmill training. First, spending too much time on the perfectly even surface of a treadmill can allow one’s stabilizer muscles in the ankles and hips to atrophy, leaving athletes more vulnerable to injury when running on more typical road conditions. Second, I have found that the belt speed of various treadmills even of the same make/model in the same gym can be very different from what they project on-screen and to each other. For this reason, I have historically set my treadmill speed based on the reading of my Stryd footpod, which I use as my standard of comparison.

In my next post, we will explore the various mistakes and setbacks I have encountered along the way in my journey to Kona as well as what I learned in process. In the meantime, for those of you who would like to follow my training progress, most of my sets can be found on my Strava account at: https://www.strava.com/athletes/15134014.

#dacakeisalie