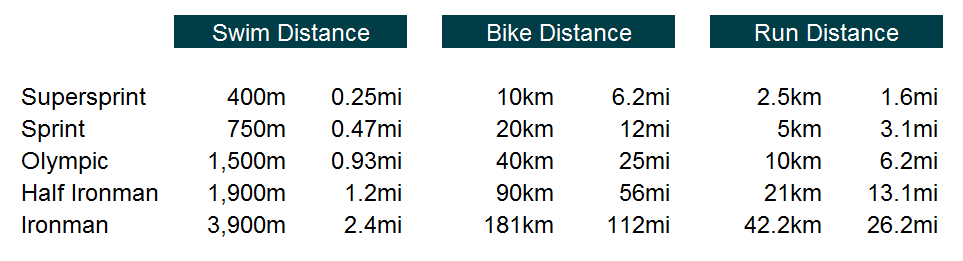

Many of you have probably been wondering about the meaning behind the title of this blog: “Project 570”. This stands for my goal time of 9.5 hours, or 570 minutes.

Wisconsin Race Report

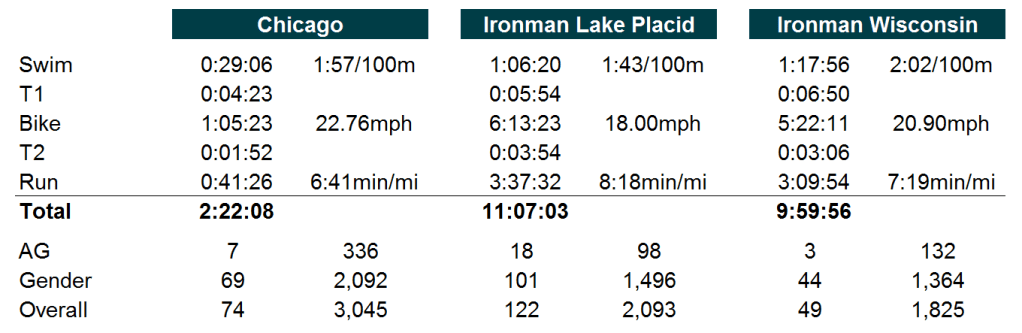

As a quick aside, a summary of last year’s race will hopefully provide some useful context to the thought process behind this goal. Having accumulated valuable race experience from Chicago and Lake Placid, IM Wisconsin was my first concerted attempt at a Kona qualification. The timing was fortuitous, as this was my last year in the 25-29 age group, after which qualifying times tend to drop drastically, primarily driven by an influx of retired pros into the age group circuit (the difference between the 25-29 and 30-34 age group winners this year was over 35 minutes!). My goal heading into the race was to break 10 hours, based on research which indicated that the 25-29 age group had historically been allocated 3 Kona slots and the average time to podium had been around that mark.

Things got off to a rocky start on the swim, as high winds and choppy water conditions created separation between the strong swimmers and the mere mortals. Due to inadequate preparation for such conditions, I exited the water with a 20 minute deficit to the race leaders, having clocked a disappointing time of 1:17:56, substantially slower than the previous year. Nevertheless, improvements to sustainable power in the saddle over the past season paid significant dividends on the bike course. A breakout performance on what is considered one of the toughest bike courses in the Ironman circuit was enough to propel me from 43rd to 8th place over the course of 5:22:11 and begin the marathon with fresher than expected legs. Prior to the race, I had made the request to my family, who had graciously come to show their support, to not inform me of my splits relative to the competition. Nevertheless, with 6 miles left in the marathon, I discovered that they had decided to break that promise when my father sprinted alongside shouting that #3 was only 2 minutes ahead and was losing ground at a rate of 20 seconds per mile. As physically exhausted (and I will admit – annoyed!) as I was at that moment, I fully credit this call for providing me with the extra push to the finish line, clocking the fastest run in my AG of 3:09:54, which was enough to snag the podium by a mere six seconds and break 10 hours by four. A summary of these results can be found below.

Kona Goals:

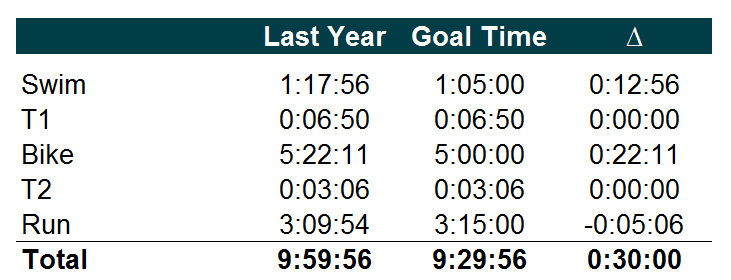

With this context in place: my 9:30 goal represents a 30 minute / 5% reduction vs. last year. While Kona is not traditionally regarded a race that is conducive to setting PBs, I believe that my limited background in the sport means that I have not traveled too far down the diminishing return curve and that there remains room for incremental improvements. As many of you know from your own endeavors, goal setting can be a tricky business, as one needs to walk the tightrope between leaving money on the table effort-wise and setting a bar that ends up being a crushing burden. This is particularly the case for Ironman races due to the presence of so many outside factors, including but not limited to adverse weather conditions, mechanical failures, and training / racing accidents. As such, this 9.5 hour goal is by no means ironclad and will be subject to the circumstances leading up to and during the race. Regardless of whether Madame Pele decides to help me or humble me, this goal has been carefully pegged at a minimum to provide a benchmark to strive towards and to provide a sense of accountability throughout the training process.

A breakdown of this goal is summarized below. Note: A more comprehensive overview of various training metrics, benchmarks, and acronyms will be provided in a subsequent post.

- Swim: A material amount of the improvement over last year’s time has been attributed to the swim. My post-race analysis attributed my underperformance to two factors: (i) a breakdown of swim technique leading up to the race due to a faster-than-optimal ramp in volume, and (ii) inadequate preparation for choppy conditions, which resulted in a total swim distance of nearly 5,000m instead of the official 3,900m (check out the jagged line in the below GPS track)! The good news is that both of these issues are low hanging fruit and are being addressed by working with a swim coach to develop my stroke and actively seeking windy days out in the open water come spring/summer. While I am currently capable of 1:30/100m in the pool (approximately a 1 hour ironman swim), given the potential for very choppy conditions and the fact that Kona prohibits the use of wetsuits, I have conservatively set a goal pace at 1:40/100m, or a goal time of 1:05.

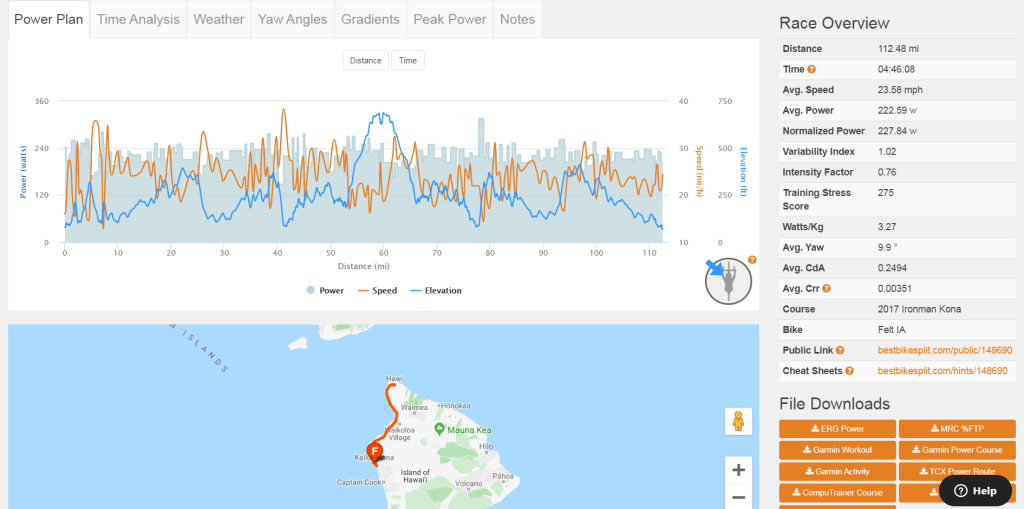

- Bike: Last year’s breakout bike performance was achieved by training my functional threshold power (“FTP”, or maximum power sustainable over an hour) to 290 watts, a substantial 30 watt / 12% gain over the prior year. While subject to the law of diminishing returns, I believe that a modest bump to 300 watts (3.5% gain) should be reasonably achievable over the following year on a similar volume of training. Crunching these numbers through BestBikeSplit’s online algorithm yields a predicted time of 4:46, driven partially by the FTP increase but mostly due to the fact that Wisconsin is generally regarded to be a more technical and hilly course. However, given the notoriously hot and windy conditions of the Kona bike course (gusts have been recorded north of 60mph), this estimate has been trimmed back to a goal time of a nice and round 5:00, representing a PB time reduction of 22 minutes.

- Run: The marathon has historically been my strongest of the three disciplines, and given my limited background in the sport, likely still has room for incremental improvements. Again keeping in mind the law of diminishing returns, breaking 3 hours seems comfortably achievable in race conditions similar to Wisconsin and a similar volume of training. This would equate to a bump in pacing from 7:19/mi to 6:52/mi. However, the heat and humidity in Kona (particularly in the infamous energy lab) will likely be a significant performance limiter, so I have trimmed these numbers back to 7:30/mi, resulting in a goal time of 3:15, approximately 5 minutes slower than last year

- T1/T2: these are difficult to predict and are dependent on the setup of the transition area, so for the sake of conservatism, have assumed the same times as last year.

Inspiring Ironman Stories

To be clear, these goals are by no means fast or particularly noteworthy. By comparison, in what has generally been described as the perfectly executed race this past October, Jan Frodeno (aka “Frodo/Frodissimo”) broke the Kona course record with a blistering time of 7:51:13. What made this performance even more special was that Jan had spent most of the year recovering from a sacral fracture.

On the women’s side, few athletes have dominated the sport as much as Daniela Ryf (aka the “Swiss Miss” or the “Angry Bird”), who has won four out of the last five Kona races. Perhaps her most impressive performance was in 2018, when after being stung by jellyfish in the swim and losing almost 10 minutes to the race leaders, she ended up storming the field and breaking both the bike course and overall course record with a time of 8:26:18.

That is not to say that fast times are the only measure of success in Kona. Perhaps one of the most iconic moments in Ironman history was the famous “crawl” of Julie Moss. 23 years old at the time and competing as part of her exercise physiology thesis, Julie found herself leading the 1982 edition of the race. Due to dehydration and fatigue accumulated over the course of the day, she collapsed a mere fifteen feet away from the finish line. Watching victory slip away as Kathleen McCartney ran past her, Julie inched toward the finish line on her hands and knees in an inspiring display of grit. Her struggle to finish the race was broadcast around the world and is not only considered one of the key factors that drove participation in the races’ early days, but is also memorialized in Section 6.01 of the race rules: “Athletes may run, walk, or crawl”.

Or take Sister Madonna Buder (aka the “Iron Nun”), who completed her first Ironman at age 55 and 45 races later holds the record as the oldest woman to ever finish an Ironman distance event at the age of 82. Her story is featured in the below inspirational (and hilarious) 2016 Nike ad.

Or Jon “Blazeman” Blais. Diagnosed in 2005 with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (“ALS”), a terminal disease with no current cure that slowly leads to full paralysis, Jon was given two years to live. As a lifelong multi-sport athlete however, Blais determined that he would race at Kona that year, declaring “I’m going to finish under my own power or they’re going to have to roll me across the finish line.” Despite already having lost some control of his body, he did just that, rolling across the finish line not long before the midnight cutoff in a defiant stand against the hand he had been dealt. Jon passed away in 2007. Athletes continue to honor him to this day at the finish line with the “Blazeman roll”.

These are but a handful of the many inspiring stories that have arisen from the Ironman circuit. Every November, as part of its Emmy-award winning coverage of the year’s race, NBC takes the time to showcase the unique and oftentimes tear-jerking journeys of individual athletes who have overcome great adversity to toe the start line. Stories such as these capture the true spirit of Ironman, celebrating what the human mind and body are capable of no matter the circumstances thrown against them.

In my next post, I will provide a high-level overview of the training plan that I have laid out in preparation for next year’s race.

#dacakeisalie